NWAL holds two climate workshops in New Mexico

In September 2018, members of the Native Waters on Arid Lands (NWAL) project team held climate change workshops at the Jicarilla Apache Nation Reservation and Navajo Technical University in New Mexico. The purpose of these workshops was a) to share and discuss NWAL climate data and projections for each reservation, and b) to learn about climate adaptation plans, needs, and challenges faced by tribal members in each region.

Jicarilla Apache Nation Reservation – September 5, 2018

On the Jicarilla Apache Nation Reservation, located in northern New Mexico near the Colorado border, an ongoing drought (currently ranked by the U.S. Drought Monitor as levels D3 and D4, the two most severe categories) has made farming and ranching extremely difficult – and in future years, climate change is expected make conditions even more challenging.

“The Jicarilla Apache Nation is located in the Rio Grande River Basin, which is the most vulnerable river basin to drought and climate change in the western United States,” said Trent Teegerstrom, Co-PI for Native Waters on Arid Lands. “Members of this tribe are already feeling climate changes and they are having to adjust how they are managing their cattle and their wildlife.”

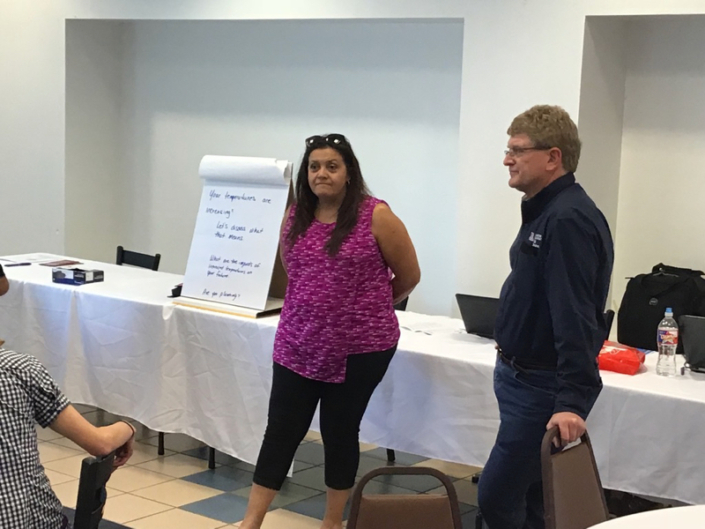

At the Jicarilla climate change workshop, which was attended by approximately 20 members of the Jicarilla Apache Nation, NWAL team member Christine Albano shared detailed climate data and projections for the Jicarilla Reservation that extend through the year 2100. NWAL team members Trent Teegerstrom and Staci Emm led discussions with the group about the impact of the ongoing drought on agricultural and livestock operations, and concerns about future climate change in the region.

“At our workshop, we shared climate data that was downscaled to the Jicarilla Apache Nation Reservation, and I think succeeded in helping them understand what is projected for the future,” McCarthy said. “In the process, we learned a lot about the very real challenges that this tribe is facing and how the projected future changes in climate may impact them.”

Photos from Jicarilla climate change workshop:

Navajo Technical University – September 6, 2018

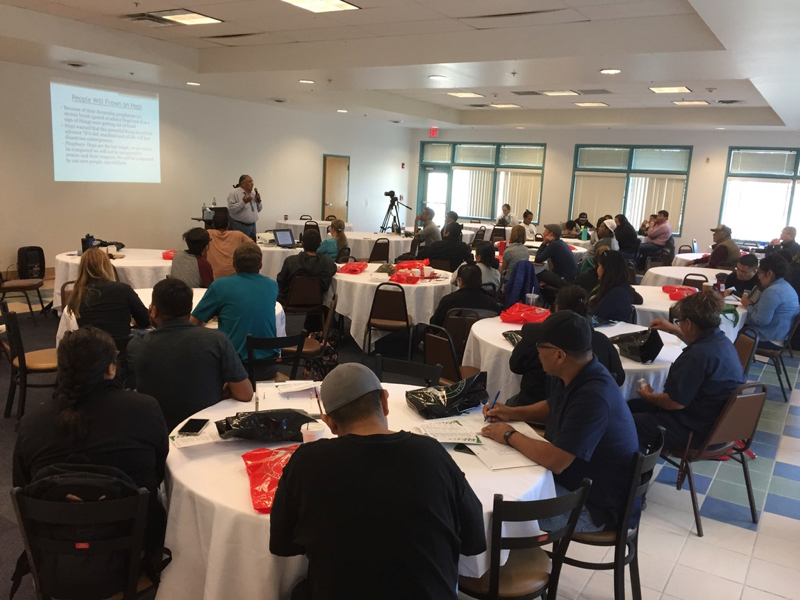

At Navajo Technical University (NTU), located in Crownpoint, NM, approximately 85 people gathered for NWAL’s climate change workshop on September 6th. The group consisted of students and faculty from NTU, and high school students from Navajo Preparatory School in Farmington, NM.

This workshop, organized by NWAL team member Steven Chischilly of NTU, included a presentation about Hopi traditional cultural perspectives on climate change, a talk about the impacts of climate change on Pinyon Pine of the Colorado Plateau, and a presentation about historic and modern climate change in the Navajo Nation and the Colorado River regions based on NWAL’s climate data and projections.

In the discussion that followed the presentations, the students and other workshop participants talked about the impacts of an ongoing, extended drought on their community and families, many of whom are involved with agriculture and livestock production on the Navajo Nation. Although many people from older generations tell stories of the large snowstorms that once occurred in this region – sometimes with as much as 4 or 5 feet of snow – none of the younger students present at the workshop could remember a time when something like this had happened.

“Navajo has essentially been in about a 12-year drought, and most of the high school students at the workshop were about 15 years old,” McCarthy said. “They have no recollection, personally, of life before this drought – so what climate change means for them is really different, because they don’t have a personal connection to times when there was snow or plentiful amounts of water.”

Workshop participants expressed a great awareness about climate change, and participated in an extensive discussion about interactions between climate and ecology of the region, added NWAL team member Meghan Collins.

“They asked great questions, and we had great dialog about adaptation of farming techniques, technology, policy and water rights,” Collins said. “It was a very insightful and thoughtful group.”

Chaco Canyon Field Trip

Chaco Canyon Field Trip

In the afternoon, about 20 of the workshop attendees took a field trip to the nearby Chaco Canyon National Historic Park. Here, NWAL team member Kyle Bocinsky, Ph.D., led a hike and discussion about historic climate change and the culture that created the sophisticated pueblos of the region – all set against the spectacular backdrop of Chaco Canyon.

“The trip to Chaco really helped the workshop participants contextualize future climate resilience within the centuries-long Native American presence in the San Juan basin,” Bocinsky said. “The environment of Chaco Canyon seems to the newcomer to be a terribly difficult place to do agriculture, but the people of Chaco successfully did so for hundreds of years. It was great to brainstorm with the workshop participants about the different strategies the Chaco people used to maintain a resilient agricultural system in Chaco Canyon, and how those strategies relate to food resilience of Native American communities today.”

Overall, NWAL’s program director felt that the climate change workshop at NTU exceeded the goals that the team had going into it.

“A major goal of the Native Waters project is to help build capacity to transfer knowledge from NWAL to Tribal Colleges, and I think we really made inroads into that here at NTU,” McCarthy said. “We had great discussions with the students and faculty, and really felt like we had the opportunity to make connections to them that were real in their lives, from modern-day impacts of climate change on agriculture all the way back to ancient times, and how that connects to their current culture.”

Photo gallery from NTU workshop and field trip to Chaco Canyon National Historic Park

Native Waters on Arid Lands is funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Partners in the project include the Desert Research Institute; the University of Nevada, Reno; the University of Arizona; First Americans Land-Grant Consortium; Utah State University; Ohio University; United States Geological Survey; and the Federally Recognized Tribal Extension Program in Nevada and Arizona.